Rutherford Heraldry

Rutherford Heraldry

Rutherfurd of Edgerston

Arms of the Clan Chief "Argent, an orle gules, and in chief three martlets sable, beaked of the second."

motto: "Nec sorte nec fato" - "Neither by chance nor by fate"

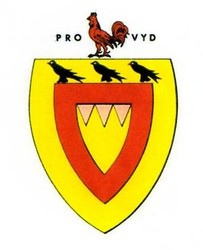

Rutherford of Hunthill

John Rutherford I of Hunthill [1510 - 1577]

"Or, three passion nails within an orle gules, and in chief three martlets sable, beaked of the second."

motto: "Provyd" - "God provides all that is needed"

These are the arms of our ancestor John Rutherford I of Hunthill

John Rutherford I of Hunthill (c.1510-1577) "Who succeeded in 1529 was then a minor, as the Treasurer's accounts for 1530 mention a composition for his relief and marriage. On March 12, 1529/30 he was seised of Nether Chatto and other lands and four marklands of Scraisburgh that were in the king's hands since Martinmas.

In 1536 John Rutherford of Hunthill shows a fess charged with three martlets.

The Roxburghshire inventory of the Royal Commission on Ancient Monuments for Scotland includes (No.441) a late medieval carved stone panel built into the north-west wall of Hunthill House: "At top and sides there are little paterae; the upper corners contain rosettes and the lower ones sprays of foliage. The shield is charged: Within an orle, three Passion nails and in chief three martlets, for Rutherford of Hunthill and Chatto".

Rutherford of Hundalee

Nicholas Rutherford II [1565 - 1628]

"Argent, an orle or within an orle gules, and in chief three martlets sable, beaked of the second."

motto: "Provyd" - "God provides all that is needed"

Nicholas Rutherford II of Hundalee (c.1565-c.1628) was the laird who was prominent in the Battle of Redesdale in 1598 for which he was sent to Edinburgh Castle in 1600. He signed a band for good order in October 1602, but was put to the horn in 1607 for not paying his share of the minister of Jedburgh's stipend and in 1608 for debt to Marion Lumisdane, Lady of Mellerstains. A month after he was appointed to fix the price of boots and shoes at Jedburgh, the Earl of Mar [Lord Erskine] named him in June 1608 among many kinsmen who refused to move from his Nisbet property.

On September 5, 1615 he witnessed Robert Rutherford's service as heir to Edgerston. Lord Grey in 1603 bought from Nicholas Rutherford 'of Gundullis in Scotland' his share of Paston township in Kirknewton, Northumberland; how Nicholas acquired it is unknown.

Nicholas II married Martha daughter of Andrew Stewart, Master of Ochiltree, by his wife Margaret daughter of Henry Lord Methven. She outlived him and married secondly Uchtred Macdowell of Garthland.

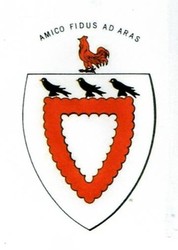

Rutherford of Fairnington

George Rutherford III [1560 - 1622]

"Argent, an orle gules engrailed, and in chief three martlets sable, beaked of the second."

motto: "Amico Fidus Ad Aras" - "Good friends are a refuge"

George Rutherford III of Fairnington (c.1560-1622) was probably George of Fairnington on a retour at Jedburgh in June 1600. George III was the laird who in 1615 saw Robert Rutherford of Edgerston's service as heir, shared in Thomas Rutherford of Hunthill's pistol fray in 1601, subscribed to a band of loyalty in 1602, was caution for the Rutherfords of the Tofts in 1611, and went before the Council in October 1617 to undertake responsibility for his tenants and servants.

In 1622 Thomas Earl of Melrose successfully petitioned that George Rutherford of Fairnington should pay 26s. due as a vassal of the Melrose Abbey estate.

"The Rutherfords in Britain: a history and guide" by Kenneth Rutherford Davis Alan Sutton Publishing Gloucester 1987

The Crest

The crest is the oldest of armorial bearings having its origins in ancient Greece and Rome. In heraldry it is represented attached to the top of the helmet or above the shield. Originally the crest was the ornament of the helmet, or headpiece, and also afforded protection against a blow. In the early rolls it was scarcely noticed, but in later armorial grants it came into general use. In the early days of the crest it was given only to persons of rank. The blazon for the Rutherford crest, "A marlet sable beaked gules" means "a black martlet with a red beak." The various branches or cadets of the Rutherford family were identified in battle by the crests which they carried. All Rutherfords used the same basic arms, but employed 'difference' at the crest to specify a particular Rutherford cadet.

The Wreath

The wreath or torse is a set of twisted cords colored with the principal metal and color of the shield The wreath is situated above the shield and/or helmet and below the crest.The wreath being a twist of two silken cords, one colored like the principal metal and the other like the principal color in the arms, presents two options for the Rutherford arms. The tincture/color of the cords would be argent [either silver or white] and gules [red].

The Motto

The motto is a phrase or sentence alluding to the family, the arms, or the crest. Sometimes the motto was a traditional war cry, especially among the Celts, which was common in the days when each chief tenant and baron under the crown brought into the field and led his own tenants and retainers into battle. It is written on a scroll above the crest or below the shield. Mottoes are often written in Latin, French and English. In Celtic countries it is not unusual to find mottoes in the native Gaelic language. The motto has some connection with the name of the bearer, the deeds of his ancestors or as sets forth some guiding principle or idea. Mottos, like arms, were sometimes punning. The Rutherford motto, "Nec sorte nec fato" - "Neither by chance nor by fate" has few equals.

The Mantle

The mantle originally was a representation of the piece of cloth that protected the helmet from the heat of the sun. It became more decorative and was usually shown in the principal colors, usually a metal and a color of the shield. The Rutherford mantle is tinctured gules or red.

The Tinctures

The colors used on coats of arms are relatively few. They are called "tinctures".

The colors and their meanings:

Or (yellow or gold) - Generosity and elevation of the mind Argent (white or silver) - Peace and sincerity Gules (Red) - Warrior or martyr; Military strength and magnanimity Azure (Blue) - Truth and loyalty Vert (Green) - Hope, joy, and loyalty in love Sable (Black) - Constancy or grief Pupure (Purple) - Royal majesty, sovereignty, and justice Tawny or Tenne (Orange) - Worthy ambition Sanguine or Murray (Maroon) - Patience in battle, and yet victorious

“Heraldic Symbolism and Convention” Edward Geoghegan

The Rutherford Coat of Arms continued...

The eagle and the bull were also early charges for the Rutherford family.

"An Aymer de Rotherford of the county of Roxburghe also rendered homage for his lands in the same year [1296], as also did Mestre William de Rotherforde, persone of the church of Lillesclyve. The seal of the former bears an eagle displayed and the legend S'Aimeri de Rotherford, and that of the latter bears a wild bull's head cabossed, a human head between the horns. And the legend S'Will'mi de Rothirford."

and.......

"a wild bull's head cabossed, a human head between the horns" - cabossed means the animal's head is facing front, with no neck showing - in essence, the bull's "face" with a human head above the bull's head & between the bull's horns. A wild bull would have long horns, curving upwards like a bison's horns only longer ( ) which creates a space between the horns. The legend "S'Will'mi de Rothirford" follows the typical pattern: "S" is an abbrev for "sigil" or "sigillum" which is Latin for "seal" or "seal of..." "Will'mi" is abbrev for the Latin (or latinized) version of William, using the apostrophe to show some letters are left out - rather like "Rob't" for "Robert" in modern useage. "de" is "of" - i.e. the family name, being a place name, refers to the family "of" (signifying ownership) the lands or place named "Rothirford" As to why the two Rutherfords you cited - apparently brothers" - used different arms: arms were originally personal, & gradually came to be inherited, but this didn't happen overnight. Relatives might well have used different arms for any number of reasons - arms of mother's or spouse's family, especially if a younger son inherited that family's lands; or they might adopt arms similar to their feudal superior; or the abbot may have used arms somehow associated with his abbey, since that was his "claim to fame" & the only reason the English would care enough to force him to sign & seal the submission. As heraldry evolved, the "family" arms (father's, grandfather's etc) came to be used, preferably with some minor "difference" (frequently a border) if a younger son, & clerics would "impale" family arms with those of their abbey or bishopric, but this wasn't established as early as 1296. "The Surnames of Scotland Their Origin, Meaning and History", by George F. Black 1946.

The Rutherford Mottos

The "nec sorte, nec fato" motto is from the Edgerston Rutherfurds [note spelling] who are the dominant line and clan chiefs of the Rutherfurds and Rutherfords. Edgerston is about 7 miles south of Jedburgh in Roxburghshire County. It's charter was granted to the family in 1492 and 1498.

The Rutherford [note spelling] mottos from the other descendant cadets [family groups] are different. North of Edgerston and quite close to the city of Jedburgh are the Hundalee and Hunthill estates - traditional holdings of the Rutherfords. Their motto is "Provyd" [provide] which comes from the Royal Stewarts from which this group descends.

In 1536 John Rutherford of Hunthill shows a chequey fess charged with three martlets, and in 1529 Margaret Rutherford, wife of Nicholas Rutherford, shows three birds with wings elevated. At the same date, Nicholas Rutherford shows the three martlets on a chequey fess.

The cadet of Rutherfords at Fairnington is quite close to the ancestoral village of Rutherford on Tweed. Their family motto is "Amico fidus ad aras" [true friends are a refuge]. Fairnington is the only Rutherford estate with a Celtic stone circle on its grounds. Fairnington was a gathering place for our people for many hundreds, if not thousands of years. This gathering spot predates the very origins of the name "Rutherford". The other major Rutherford cadets all have their origins in one of the cadets already mentioned. The Fairnilee and Castlewood cadets come from Edgerston, so they share the "nec sorte, nec fato" motto and coat of arms. The cadets of Chatto, Townhead, Nisbet and Hall all come from the Hunthill Rutherfords so they use "Provyd".

All cadets of Rutherford arms should have an "orle gules" or red shield. The birds should be "martlets sable" i.e. black martlets. The martlets should be "beaked of the second" i.e. they should have red beaks.

The Rutherford blazon or heraldic description cannot be varied in it's basic layout by any Rutherford/Rutherfurd cadet - "Argent, an orle gules, and in chief three martlets sable, beaked of the second." Cadets distinguish themselves by variations in the border of the large shield/escutcheon or the orle itself. Each cadet could also use a different crest to make distinction of their group. The common crest is a black martlet. The Fairnington and Hunthill cadets use a red rooster [from the Clan Gordon] and the Hundalee cadet uses a human head [from the Clan Gladstane] along with passion nails [from the Douglases of Morton]. The three passion nails, refer to the three nails used to fasten Jesus to the cross.

The “shield upon shield” Families

Two coat of arms with an "orle gules": Sir Walter de Lindsay and Sir Alexander de Balliol of Cavers. Sir Walter de Lindsay is an ancestor of the Rutherfurds of Edgerston and Cavers is quite near Jedburgh, Roxburghshire. Not surprisingly, Sir Walter de Lindsay and Sir Alexander de Balliol had strong connections with the Cistercian monastic order. Kenneth Davis Rutherford in his "The Rutherfords of Britain - a history and guide" theorizes that the Rutherford orle came from the Balliol family, who also had strong connections with the Cistercian order. However, only the Balliol orle of Sir Alexander de Balliol is red, the traditional Balliol charge is argent [white].

The Balliol family also came to England and later Scotland with William the Conqueror. They also fought under the flag of the Counts of Boulogne [Boulonnais]. Their heraldric charge is the reversed tinctures of the de Wavrin family [and identical to the Rutherfords] which was effected following the marriage of Baildwin of Bailleul, castellan of Ypres to Agnes de Wavrin sometime in the 1130s.

Note that the tinctures [colors] of the coats of arms mentioned above are all "gules and argent" white and red. The earliest of Flemish coats of arms were centered more on tincture than on the images [charges] displayed on the shield. These colors were/are indications of ethnic and regional origins in Flanders. The Rutherford cadets of Hunthill and Hundalee still carry coats of arms in the "gules and or" [red and gold] of the noble family of Boulonnais. The Counts of Boulogne [Boulonnais] were the feudal overlords of the seigniory of the Court of Ruddervoorde. The most famous member of this family was Count Eustace II of Boulogne, companion and in-law of William the Conqueror.

Martlets were/are used as signs of cadency or birth order for male descendants. Today these symbols are used by all families in a uniform way, but they were born in Flanders and again more precisely with the Boulonnais family. The martlet was used in the 12th century only by the Boulonnais family as an indication of birth order, i.e. the forth son of the Count of Boulogne. At the time of the Flemish introduction into Roxburghshire the bearer of that sign was Ernisius de Seaton [Seton] crossbowman to King Henry I of England.

William I used archers and crossbowmen at Senlac, depicted on the Bayeux tapestry which shows Eustace, count of Boulogne and members of the Flemish families of Senlis, St. Pol, Hesdin and Alost being led by an archer probably a crossbowman of Lens. The square red brick tower of the guildhall of the crossbowmen of St. George and St. Denis in the Ecole Normale and that of the archers of St. Sebastian in the rue des Carmes in Bruges, Belgium still stands. The surname Crossbowman or Balistarius appears in many parts of Britain - in Surrey (East Molesey), Norfolk (Barningham Winter), the Midlands, Cumbria and Devon.

Ever since the Conquest, land had been held for military or other services. Property was held for a certain number of knight's fees and the landowner had to provide that number of knights, archers or crossbowmen for the royal army when called to do so - fines and scutages were levied on those who did not go on the king's service.

"The Rutherfords in Britain: a history and guide" by Kenneth Rutherford Davis Alan Sutton Publishing Gloucester 1987

“The Rutherfords of Roxburghshire” Gary Rutherford Harding 6 editions from 1918 to 2002 privately published

The Rutherford Coat of Arms

The origin of heraldry was not Norman but Flemish. The Normans were not in a position to know about the symbolic devices of Charlemagne's court. It is most likely, therefore, that the origins of English and Scottish armory are to be found not in Normandy (the Normans were of mixed Scandinavian and Frankish descent), but in the system adopted by certain ruling families descended from the Emperor Charlemagne, the military and political colossus who ruled the Frankish Empire of northern Europe from 768 to 814. These families perpetuated much of the administrative organization of the Carolingian Empire, including the use of dynastic and territorial emblems on seals, coinage, customs stamps and flags. There is evidence to suggest that these devices were common to families or groups linked by blood or feudal tenure, and were of necessity hereditary. With the redistribution of lands following the Norman Conquest, the cadets in England of Flemish families who were of Carolingian descent, and the devices used by them, became integrated in Anglo-Norman society. During the first Crusade, only thirty years after the Conquest, the mass cavalry charge of mail-clad knights remained the standard tactic of warfare. Order was maintained in the ensuing fight by the use of mustering flags bearing the personal devices of commanders and it is clear that these were sufficiently distinctive to be recognized, even in the heat of battle. It is likely that they also possessed a peacetime function - that of marking territory and symbolizing authority - and that the devices used for this purpose also came to be engraved on seals by which documents were authenticated. The proto-heraldic devices were displayed, not on shields at that stage (many similar shields are shown on the Bayeux Tapestry but rather on seals and banners. Hereditary devices may have been known in 1066, and symbolic banners seem to have been carried at the battle of Hastings and in the First Crusade.[Department of Medieval Studies at the Central European University-Budapest]

If the undoubted links of the ruling families of Flanders with Charlemagne had any heraldic connotations, the political decline of Flanders in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries and the misfortunes that overwhelmed its ruling houses, would have given their descendants in England an additional urge to preserve their heritage and promote their armorial devices. Whatever its origins, it is clear that what had been, in the late eleventh century, the inheritance of a small group of interrelated families in northwest Europe, spread through the upper ranks of society in the twelfth century. This widespread adoption of colorful devices and symbols was one aspect of the twelfth-century renaissance. Once symbols were transferred to the shield, they gave rise to what is accepted as heraldry, and this practice spread across Europe in a period of less than thirty years.

Coats of arms probably originated during the 1st Crusade in 1097. According to most authorities, the Europeans who took part in this march to secure the Holy Land from the Turkish Saracens were surprised to learn that the Asian warriors employed military tactics far superior to anything previously seen in Europe. A peculiar characteristic of the Asian armies were the use of shields marked by designs and colors. Beaten in Asia Minor, the European Crusaders returned home with stories of the military powers of their foes. Later the use of the designs on shields and other armor found it's way into the European armies.

Heraldry is the handmaiden of genealogy because of this hereditary usage. In medieval times the shield generally represented the family and the crest usually represented a particular son or family line. In America the democratic tradition and cries of discrimination has caused interest in armorial insignia and orgins to almost disappear. Since each arms or crest were earned in battle or given to one individual, the individual usually proudly exhibited it while fighting against enemies. Many time the Kings allowed their armies to use the King Shields. Under heraldic rules only the first sons of a first son of the recipient of a Coat of Arms are permitted to bear their ancestor's arms. Younger sons may use a version of their father's arms but must be changed somewhat. If the bearer of a coat of arms dies without male heirs his daughter may combine her father's arms with her husband's arms. “Hyatt Family Heraldry” – William Hyatt

Originally coats of arms were embroidered on the surcoat of the armored knights. The term is now used for the shield [escutcheon] when arms are displayed. The term coat of arms is now used even when displayed elsewhere than on the coat. In the days when knights were so encased in armor that identification was difficult, the practice was introduced of painting their identifying insignia on their shields. Originally, these were only granted to individuals, but eventually were made hereditary by King Richard I, during his crusade to Palestine.

The Rutherford Blazon

"Argent, an orle gules, and in chief three martlets sable, beaked of the second."

Defined as a system of pictographic history, blazoning is the initial step in understanding the Rutherford coat of arms. Blazoning is the description of a coat of arms in the technical language of heraldry. The rules of blazon are well defined and noted for their precision, simplicity, brevity and completeness. Blazons are an ancient response to an information storage problem. It has never been easy to store vast archives of coats of arms, so heralds devised a precise written system for describing them. In this way, relatively small amounts of space were required to store large quantities of armorial data. The language of blazonry has its own vocabulary, grammar and syntax. Blazons are supposedly devoid of punctuation, but as you can see with the Rutherford blazon, many armorials or books that contain blazons use punctuation. "Argent, an orle gules, and in chief three martlets sable, beaked of the second."

A blazon has a proper order of describing arms:

i. Give the field, its color and the character of any partition lines

ii. The charges, and first those of most importance, their name, number and position

iii. Marks of difference, cadency or baronet's badge

Repetition is studiously avoided in the language of blazonry. If you look at our blazon you will see a good example, if two charges [figures] have the same color the second is described as "of the first", "of the second", etc. depending on where in the blazon the color is first mention. So "beaked of the second" does have a precise meaning in blazonry. We'll discuss and translate our blazon in the following article bit by bit.

The Achievement of Arms

The complete design ensemble of a coat of arms is called an achievement of arms and can be broken down into the following component parts.

The Shield

The shield or escutcheon is the most important part of the coat of arms and displays the primary heraldic symbolism of the arms. The escutcheon of the Rutherford arms is usually in the shape of a shield. It originally represented the war shield of a knight, upon which his arms were displayed. Indeed, the escutcheon may be the only component of many coats of arms. The shield or escutcheon is also known as the field. It's upon this "canvas" that the charges or bearings [figures] are blazoned [painted]. So in our Rutherford blazon the first word "Argent" refers to the shield, escutcheon or field. Argent simply means silver, but the convention for actually painting the shield made the use of white paint synonymous with silver. So what it says is "the shield is silver or white". Argent [the root of the word Argentina] also stands for peace and sincerity. There's a basic guide to the colors or tinctures, along with their meanings, at the end of the article.

The Charges

Charges are the figures or anything occupying the field of an escutcheon. Some coats of arms are divided into geometric partitions, the Rutherford arms are not. Most coats of arms include symbols or "charges". Many of these symbols consist of fairly simple geometric shapes known as ordinaries and sub-ordinaries. The Rutherford arms employs a sub-ordinary called an "orle". An orle is a smaller shield-shaped figure or charge within the larger shield itself. This is where we can return to our blazon and see the next phrase, "an orle gules". This simply means "a red shield". Gules is another tincture or color meaning red or bloody. The orle stands for preservation or protection and when coupled with the color red [gules] signifies military strength and magnanimity. A red orle also echos the arms of another important Scottish family; the Balliols. The Rutherford arms contains an orle which is the principal armorial figure of the family. By some it is taken as an inescutcheon voided or cliche' that is, it is redundant, the orle repeats the basic shape of the shield. The orle was used in the arms of those who had given protection and defense to their king and country. It may be interpreted as a sign of those families who were very active in defending the Borders. The Rutherfords were defenders of the Scottish kingdom, under the Balliols, against the English.

The Royal Tressure/Orle as it is called has now become the prerogative of the royal family and families that are descended from it in female line. Yet it is also used as an augmentation of honour. Woodward states: "As early as the middle of the fourteenth century we find several families of mark bearing the tressure without having any connection with the Royal House..." (Flemings of Biggar, William Livingston, house of Seton) "James V in 1542 granted a warrant to Lyon to surround the arms of John Scot, of Thirlstane, with the royal Tressure, in respect of his ready services at Soutra Edge with three score and ten lances on horseback, when other nobles refused to follow their sovereign." It has been at least twice granted as an augmentation to the arms of foreigners: James V to Nicolas Canivet of Dieppe in 1529, and James VI to Sir Jacob van Eiden, a Dutchman. Innes of Learney also cites Dundas of Fingask (1769) and Wingate (1930) as recipients of the tressure for distinguished services. The word tressure [braid] seems to come from tailoring, like orle [hem]. “Tressure and Orle”, Heraldic, 1995-2003, François R. Velde

The field also contains three martlets, "and in chief three martlets sable, beaked of the second". "Three martlets sable" would indicate that the martlets are black and "beaked of the second" means that the martlets have beaks that are colored the same as the second color mentioned, i.e. red [gules]. "In chief" would indicate that the martlets are displayed at the very top of the shield. Martlets are not blackbirds or crows, they are mythological birds resembling a swallow, but having short tufts of feathers in the place of legs. A more contemporary idea is that the birds are Choughs, a bird once found on the banks of the River Jed and Tweed, but blazoned as 'martlets'.

The use of the martlet as a charge has two basic meanings in the symbolism of heraldry. The first and most common association is with service in the various crusades in the Middle East and Iberia. The heralds of continental Europe claimed that the beaks and legs were lost in the Holy Land fighting the Muslims. Presumably they were adopted by ancient warriors to signify their surviving a crusade. In England the martlet tends to keep its beak, and the Scottish author of "A System of Heraldry" published in 1722, Alexander Nisbet [a Rutherford descendant and Clan Hume member], stated that in England they also kept their legs, although these were very short. As you can see, all three Rutherford martlets have both red beaks and no feet.

The martlet has a second significance. When the martlet is used as a 'difference' on the shield, it indicates that the bearer is the fourth born son of the owner of the coat of arms. There is, however, no documentation of a Rutherford [or three, one for each martlet] fighting in the crusades or of a 4th son of a Lord Rutherford establishing these arms. Knowing the strictness with which the Scots have historically approached heraldry, the martlets are not placed casually. It's likely that one or both of the possible scenarios is part of Rutherford history.

The Helm

The helm [helmet] was added to arms before the beginning of the 14th century and in the 16th century to indicate the rank of the bearer. The helmet is positioned above the shield and beneath the crest. In England a helmet of steel with the visor closed would indicate that the bearer of the arms was not a knight, noble or royal. However, this convention is not used in Scotland. Helmets that face forward are indications of a royal or, at least, noble family connection. The helmet in the Rutherford arms is always shown in profile facing to the dexter, that being the helm's right or the viewer's left. The various distinctions of the helmets position and metal to ascribe rank were not in use until after the enrollment of the Rutherford arms, i.e. they don't apply to arms of such antiquity.